Bladder Cancer: Common Questions & Answers

How common is bladder cancer?

It is estimated that approximately 70,000 Americans are diagnosed with bladder cancer and that 15,000 die of this cancer each year. Male patients outnumber female patients three to one, making bladder cancer the fourth most common cancer in men.

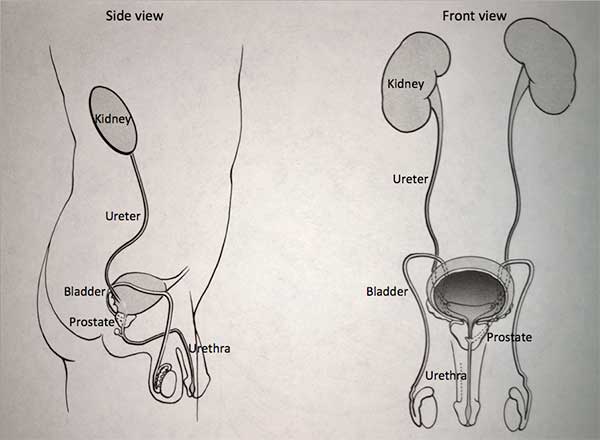

The bladder is part of the urinary system. The kidneys make the urine, which is transported to the bladder which holds the urine until full. During urination, the bladder empties the urine to the urine through the urethra, the urinary pathway.

The linings of the bladder and urinary tract are composed of specialized cells called urothelium or transitional cells. Over 90% of bladder cancer cases involve this lining and are referred to as urothelial cancer or transitional cell carcinoma.

What are risk factors for bladder cancer?

Smoking is the most important risk factor for developing bladder cancer. There is an approximate threefold increased risk of bladder cancer among current and former smokers. Industrial exposures to certain chemicals such as aniline dyes, which are used in the fabric industry, and aromatic amines, which are used in various industrial processes, are also linked to bladder cancer. Radiation to the pelvis and exposure to the chemotherapy agent, cyclophosphamide, have also been linked to bladder cancer.

How is the stage and grade determined?

Stage

Stage refers to the anatomic extent of the cancer. The bladder is composed of the three layers: epithelium (the “skin” of the bladder), connective tissue and muscle. The stage of the bladder cancer is determined by how deep the cancer invades into the layers of the bladder.

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (which includes Ta, T1 and carcinoma in situ) is confined to the epithelium or the underlying supporting connective tissue. In contrast, muscle-invasive bladder cancer invades into the muscle (T2) or beyond the bladder (T3) and represents more advanced disease.

Grade

Grade refers to the microscopic appearance to the bladder cancer cells. Bladder cancer is assigned a grade based on how aggressive the tumor appears on pathologic exam (once the pathologist looks at the bladder cancer cells under the microscope after it has been removed). Grades include Papillary Urothelial Neoplasm of Low Malignant Potential (PUNLMP), low grade and high grade. The higher the grade, the more likely the cancer is to recur and progress deeper into the bladder layers.

What are the symptoms of bladder cancer?

Most people with bladder cancer are diagnosed after an episode of blood in the urine (hematuria). Hematuria may be referred to as gross hematuria (seen with the naked eye) or microscopic hematuria (detected on a urinalysis test). In some cases, patients may only have irritative voiding symptoms, which include urinary urgency and frequency.

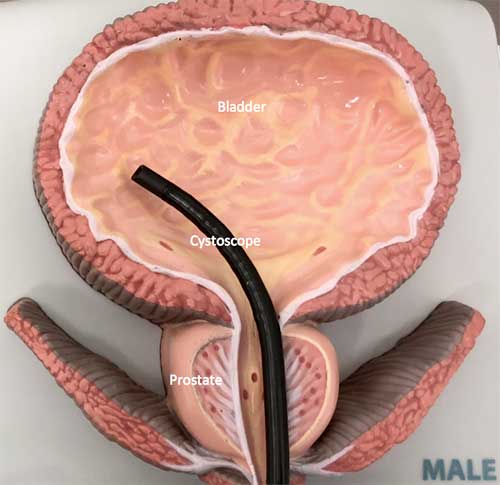

Evaluation for hematuria includes cystoscopy (look in the bladder with a camera), cytology (check the urine for cancer cells) and imaging of the kidneys and collecting system with contrast enhanced computerized tomography (CT scan, also called CT urogram). Patients who have gross hematuria require full urological evaluation.

For patients with microscopic hematuria, if they are older than 40 years, or younger than 40 years with risk factors for bladder cancer, they should undergo complete urological evaluation.

How is bladder cancer treated?

Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor (TURBT) is the standard of care for initial management of bladder cancer and serves a diagnostic and therapeutic purpose. It is done in the operating room under regional (spinal or epidural) or general anesthesia. Using the cystoscope, a fiberoptic instrument that is placed via the urethra into the bladder, the urologist can resect (remove) the bladder tumor. In some cases, a catheter may be left in place for several days to drain the bladder and allow the bladder to heal. Hazards of the procedure include bleeding, perforation of the bladder, damage to surrounding organs, fluid absorption and complications from anesthesia.

What is the management following initial tumor resection?

Subsequent management depends on the stage and grade of the tumor. Low grade, superficial tumors (Ta) can be followed with office cystoscopy and cytology every three months, with gradually increasing intervals.

High grade tumors are often managed with a re-staging TURBT, a procedure to resect more deeply at the site where the bladder tumor had been, with the recognition that up to 60% of these tumors may be understaged, or have grown further into the bladder layers than seen on the first surgery.

What is BCG immunotherapy?

Bladder cancer has the potential to recur (new bladder tumors can form) or progress (change to a higher grade, or invade into the bladder wall). Medications can be placed into the bladder to lower the risk of recurrence or progression. Bacille Calmette Guerin (BCG) is a bacteria that triggers the body’s immune system when placed in the bladder. It is first line treatment for carcinoma in situ (CIS) and is used to help prevent recurrence and progression of bladder cancer. BCG is instilled into the bladder via a catheter 2 to 4 weeks after TURBT (once the bladder has had a chance to heal). BCG induction therapy consists of 6 weekly instillations in the bladder. The BCG is allowed to remain in the bladder for one hour.

After the initial six-week course of BCG treatment is complete, additional maintenance therapy may be given for the next one to three years.

Side effects of BCG treatment may include bladder irritation with urinary urgency and frequency, and blood in the urine. Other local side effects may include inflammation of the prostate, testicle and epididymis (gland above the testicle). Systemic side effects may include fever and malaise (feeling ill). Serious side effects occur in less than 5% of patients, which may include blood infection requiring antibiotics or possibly hospitalization. In some cases, BCG therapy may not be used in patients who are immunosuppressed or on steroid (prednisone) treatments. A scheduled BCG treatment may be withheld if there is catheter trauma, urinary infection, or recent gross hematuria.

What if BCG doesn’t work?

If the bladder cancer recurs after induction therapy, or the stage or grade of the tumor worsens while on BCG treatment, this may indicate the cancer is not responding to BCG therapy. In this case bladder removal (radical cystectomy) may be considered in patients healthy enough to undergo this surgery. Performing a radical cystectomy within two years of the start of BCG therapy can improve survival compared to waiting.

How is muscle-invasive bladder cancer treated?

If the bladder cancer has grown into the muscle layer of the bladder or beyond, bladder removal (radical cystectomy) and lymph node dissection is indicated for those healthy enough to undergo the surgery. Preop evaluation includes blood work, urine studies and chest x-ray and CT scans to be sure the cancer has not spread. In men, the surgery involves removal of the bladder, and typically the prostate and glands behind the prostate (seminal vesicles). In women, the surgery involves removal of the bladder, typically uterus and part of the vagina. The surgery can be done using open (incision), laparoscopic (“keyhole surgery”) or robotic surgery. Surgery typically lasts 4 to 8 hours and involves a 5 to 8 day hospitalization.

When the bladder is removed, there has to be a new way to get the urine to the outside. Choices include an ileal conduit, which uses a loop of bowel to bring urine outside to be collected in a bag, or a neobladder, which uses intestine to create a new bladder.

How is bladder cancer monitored?

Because there is the risk of recurrence and progression of bladder cancer, ongoing follow-up is needed, which includes cystoscopy and cytology (as described above). These surveillance procedures are done three months after surgery and then at repeated intervals according to the tumor grade. High grade tumors often require lifelong surveillance. Imaging of the collecting system (such as contrast CT scan) may be done at periodic intervals depending on the tumor grade and risk factors.

Print PageContact us to request an appointment or ask a question. We're here for you.