Prostate Cancer Q&A

What is the prostate?

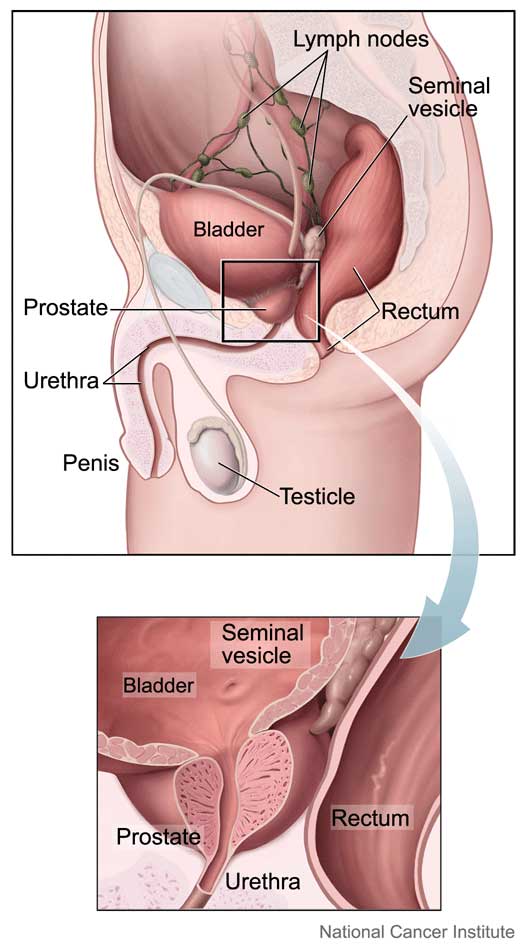

The prostate is a gland that is part of the male reproductive system. It is located below the bladder and in front of the rectum. It forms the first part of the urethra, the tube that carries urine from the bladder through the penis. The prostate makes fluid for semen.

Prostate cancer is common. It is the second most common type of cancer found in American men and the second leading cause of cancer death among American men.

What is localized prostate cancer?

Localized prostate cancer is cancer that is confined within the prostate and has not spread to other sites, which is to be distinguished from prostate cancer that has spread beyond the prostate to other parts of the body.

In general, prostate cancer tends to be very slow growing. The likelihood of developing prostate cancer increases as men get older. When prostate cancer develops in older men, it tends to be a less problematic disease.

What are the symptoms of localized prostate cancer?

As men grow older, they experience the normal age-related, noncancerous enlargement of the prostate (also known as benign prostatic hyperplasia, or BPH). As the prostate enlarges, it can crowd the urinary pathway and make urination more difficult. Once men reach the age of 40, they may start to notice changes in urination, which can include slowing of the urinary stream and increased frequency of urination both day and night.

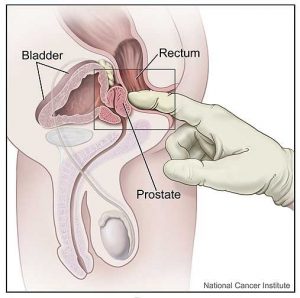

Prostate cancer, when it first begins and is in its early stages, may not cause any symptoms. Urinary symptoms may be present but they are usually due to the prostatic enlargement described above. The best way to detect prostate cancer at its early stage is with screening, which currently includes an annual digital rectal exam (also called a DRE) and a PSA blood test.

How do you screen for prostate cancer?

Current patterns of practice include two tests to screen for prostate cancer, the digital rectal exam and PSA. The digital rectal exam is a physical exam performed by a medical practitioner to feel the surface of the prostate (a lubricated, gloved finger is placed in the rectum to feel the prostate). The prostate can be assessed to determine if there may be a hard spot, or an area of asymmetry, which may be a sign of prostate cancer.

The PSA is a blood test done to measure the level of PSA, prostate specific antigen, which is a protein made by the prostate. PSA elevation is nonspecific, and an elevated PSA may be a due to prostate enlargement, inflammation (which can include urinary infection), or may be the first sign of prostate cancer. Furthermore, PSA is not always elevated when prostate cancer is present and there may be prostate cancer even with a normal PSA (which is why the DRE needs to be done too).

How is prostate cancer diagnosed?

If there is a concern that prostate cancer may be present, for example if there is an abnormal digital rectal exam or an elevated PSA, then further evaluation is carried out with transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) and prostate biopsy. For this procedure, an ultrasound probe is placed in the rectum to visualize the prostate. Needle (core) biopsy of the prostate is taken in a grid-like systematic fashion to obtain samples of the prostate. The ultrasound does not specifically show areas in the prostate that are suspicious for prostate cancer. Rather, it allows precise placement of the biopsy needle to obtain samples. Once the samples are removed, a pathologist can look at the prostate biopsies under a microscope to determine if cancer is present. Hazards of biopsy include blood in the urine, stool or semen; infection and inability to urinate.

What is tumor grade?

Grade is a term used to describe the microscopic appearance of the prostate cancer, and can help predict the potential aggressiveness of prostate cancer. Grade can be used as a measure to assess how likely a prostate cancer is to grow and spread. The grading system most commonly used is called the Gleason score, which ranges on a scale from 2 to 10. In general terms, there are five different recognized patterns of prostate cancer (five different ways it can look under the microscope). The patterns are numbered Gleason grade 1 through 5. The pathologist can indicate which of these five patterns is present. In most cases, there is more than one pattern present, so the two most common patterns are identified. The Gleason score is a summary of the two most common patterns (for example, if there are some areas of Gleason grade 3 and other areas of Gleason grade 4, the cancer may be assigned a Gleason score of 7).

From a practical point of view, clinical experience shows that most patients with prostate cancer have Gleason scores between 6 and 10. As the Gleason score increases, there is the potential for more aggressive disease. Higher Gleason scores (8 through 10) indicate more aggressive tumors which have the potential to have spread beyond the prostate.

What is tumor stage?

Tumor stage refers to the size and the extent of the cancer (how much is present). A staging system exists that quantifies the extent or volume of disease. When the cancer is low volume, and confined to a small area of the prostate, treatment outcomes are improved compared to those situations where the prostate cancer involves a significant portion of the prostate gland.

Furthermore, those cancers confined to the prostate can be more successfully treated than those that have spread beyond the prostate. Cancers that have spread beyond the prostate to the lymph nodes or bone have less favorable outcomes with treatment.

What should be considered in choosing a treatment?

Life expectancy, rather than patient age, is important to keep in mind when choosing a treatment. As noted previously, prostate cancer tends to be slow growing. For prostate cancer that is confined to the prostate, it may take several years until it spreads beyond the prostate and several more years after that before those areas of cancer spread can cause clinical problems. With the recognition that there may be a long timeframe for prostate cancer to cause trouble, older men who have other serious health problems may be less likely to suffer ill effects from advancing prostate cancer and so may not require treatment. However, for men who have a long life expectancy, who are likely to live for at least 10 more years, they are more likely to benefit from treatment, particularly if their prostate cancer is in a medium or high risk category of aggressiveness.

An assessment of a patient’s health status includes review of their current medical problems, including consideration of the seriousness of any coexisting diseases, and evaluation of the family history of medical problems. A man’s health may also help predict how likely he is to experience hazards related to treatment. Younger men are less likely to experience treatment-related changes in urinary or sexual function.

Each man has different priorities when deciding how to be treated for his prostate cancer. Some men want their cancer removed, without consideration of age, grade or stage, and are willing to face potential hazards of surgery for the chance of complete resolution of their cancer. Others may be worried about the effect of treatment on their quality of life, and choose their treatment to minimize the risk of developing unwanted hazards of treatment, such as urinary leakage or erectile dysfunction. Each man’s personal values play an important role when choosing a treatment.

Watchful waiting and active surveillance have two main advantages – low cost and no immediate complications.

In watchful waiting, the prostate cancer is left as is, and treatment is initiated if there are signs that the prostate cancer is causing clinical problems. Watchful waiting is used in men who have a short life expectancy, due to their other health problems, so they can avoid hazards related to treatment.

Active surveillance may be a favorable choice in men who have low risk disease, including those who have longer life expectancies. Factors which predict low risk disease include low Gleason score (6 or less), PSA level less than 10, and low volume disease (less than half the biopsies positive, and no more than 50% of any one biopsy core positive). Studies show that men with localized, low grade prostate cancer have a reduced risk of the cancer spreading in the first ten years after diagnosis.

The main disadvantage of watchful waiting and active surveillance is that over time the cancer may become worse and even untreatable. It is not always possible to predict when a prostate cancer progresses and spreads beyond the prostate. In men who have chosen active surveillance, and on follow-up are noted to have signs of progression of their prostate cancer, treatment can be initiated at that point, which can include radical prostatectomy or radiation to the prostate. However, the potential exists that the disease may have already spread beyond the prostate, and if so there is the potential for those men to suffer from progressing prostate cancer.

What are the treatment options for localized prostate cancer?

The three most common treatments for localized prostate cancer are expectant management, which includes active surveillance and watchful waiting, radiation therapy and surgery.

Active surveillance or watchful waiting is based on the recognition that some prostate cancers follow a nonaggressive course, and tend not to spread outside the prostate or become life threatening. PSA and a digital rectal exam need to be checked on a regular basis, and repeat prostate biopsies should be carried out at regularly scheduled intervals. If during the monitoring period the cancer shows signs of growth or of becoming a more aggressive tumor, then treatment with surgery or radiation can be initiated.

Radiation therapy, includes two types: interstitial prostate brachytherapy and external beam radiation therapy. With interstitial prostate brachytherapy, small radioactive “seeds” are planted in the prostate. The seeds deliver radiation energy to the prostate over the course of four to six months which can “kill” the prostate cancer cells. Seed treatment is an outpatient-based procedure. External beam radiation therapy uses radiation delivered from an external source (an x-ray beam) to treat prostate cancer.

Radical prostatectomy is the term used for surgery to remove the prostate. Surgery can be done through an open, laparoscopic or robotic technique. The term “radical” means that the entire prostate and nearby tissues are removed through surgery.

Other treatments, such as cryotherapy, have been used for the treatment of localized prostate cancer, but have not been widely used.

What are the benefits and risks of each treatment?

Benefits are preservation of urinary and erectile function. Disadvantages are repeated blood draws and exams, anxiety and a small risk of cancer progressing.

Radiation therapy uses radiation to treat prostate cancer. The advantage of radiation therapy is that it is less invasive than surgery. Hazards associated with treatment include urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, which may happen less frequently with radiation when compared with radical prostatectomy. Other hazards include radiation damage to the bowel and bladder. Fortunately, current radiation therapy techniques are designed to minimize trauma to adjacent structures. One disadvantage of radiation therapy is the prostate remains, so it is possible for some cancer to persist and potentially progress in the future.

Interstitial Prostate Brachytherapy is a therapy that places radiation seeds within the prostate. The advantage of brachytherapy is that it is a single outpatient anesthesia-based procedure. As with other radiotherapy treatments, erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence may develop. Changes in urination may include increased frequency and urgency, and more frequent urination at night.

External Beam Radiotherapy uses carefully directed radiation directed at the prostate in an effort to kill the prostate cancer cells. A general anesthetic is not required. Radiation treatments are given on a daily basis, five days a week, for a seven- to eight-week treatment period. Current technology allows radiation to be delivered to the prostate while minimizing exposure to adjacent structures, such as the bladder and rectum. On a side note, men who have underlying bowel disease, such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, may be less suitable candidates for radiation therapy because of the increased potential for bowel difficulty.

Both forms of radiation (prostate brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy) may cause urinary or bowel difficulty, and can predispose to erectile dysfunction. Irritative urinary tract symptoms can include urinary frequency, urgency, and pain or burning with urination. Symptoms typically resolve over time but may persist for the first several years. Bowel difficulties may include diarrhea or loose stool. Rectal pain or discomfort may also develop. Erectile dysfunction is less likely to develop in the period immediately after treatment but is more likely to develop over time.

Radical prostatectomy describes the operation to remove the prostate. Surgery is carried out under general anesthetic. Patients are in the hospital for one to three days postoperatively and are sent home with a catheter (urinary drainage tube in the bladder) which is removed after one to two weeks.

The main benefit of this operation is that it offers the potential to remove all the cancer. Treatment by radical prostatectomy offers the man with cancer that has not spread outside the prostate the possibility of freedom from the disease for the rest of his life. If the cancer has already spread beyond the prostate, then removing the prostate may not lead to cancer cure and additional therapy may be needed.

The main disadvantages of radical prostatectomy are the hazards associated with the procedure. Erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence are the problems reported most often. The chance of having erectile dysfunction depends on a man’s age and health, his sexual function before treatment, the stage of the cancer, and the ability to save the nerves that control erection during the surgery. Younger men (those under 60 years of age) are less likely to have problems with their erections than are older men. If erectile dysfunction does occur after surgery, erections may return to normal over time. There are also medications and devices to treat the problem that may also be helpful.

Unwanted loss of urine after radical prostatectomy occurs in a subset of men, but usually lessens or stops with time. Other problems associated with radical prostatectomy include irritation of the bladder, gastrointestinal symptoms, bladder infection, and blockage of the urine flow from the bladder. Rarely, scarring may occur at the junction of the bladder and the urethra and may require an outpatient procedure to address.

Introduction of the da Vinci robot has provided the surgeon with a number of advantages including increased precision, 3D visualization, increased surgical maneuverability, tremor filtering and advanced instrumentation. Compared to traditional open surgery, laparoscopic surgery results in less blood loss, decreased risk of blood transfusion, shorter hospital stay and quicker return to normal function. Learn more about Robotic Prostatectomy.

Contact us to request an appointment or ask a question. We're here for you.